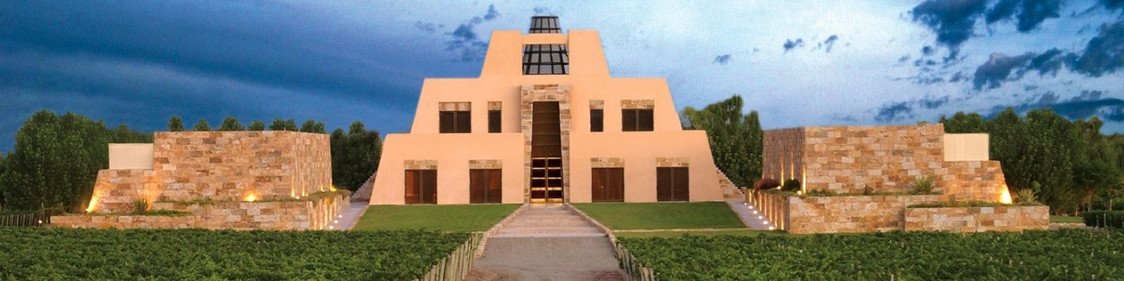

Founded in 1902, Argentina’s Bodega Catena Zapata is known for its pioneering role in resurrecting Malbec and in discovering extreme high altitude terroirs in the Andean foothills of Mendoza. In 1920, Nicolás’ grandfather Nicola Catena planted his first Malbec vineyard in Mendoza. Today, the wines of Bodega Catena Zapata are sourced from six historic estate vineyards: Angélica, La pirámide, Nicasia, Domingo, Adrianna and Angélica Sur.

Nicola Catena, Nicolás Catena Zapata’s grandfather, sailed from Italy to Argentina in 1898, leaving behind his famine-stricken European homeland for a land of plenty and opportunity. Nicola planted his first Malbec vineyard in 1902, even though Malbec had been a blending grape in Bordeaux, Nicola suspected it would find its hidden splendor in the Argentine Andes. It was a hunch that would not fully flower until nearly a century later.

Domingo, Nicola’s eldest son, inherited his father’s dream and took the family winery to the next level, building the Catena business to become one of the largest vineyard holders in Mendoza. In 1960s, however, Argentine economy imploded and inflation rates soared. Familia Catena struggled to hang on.

Argentina’s years of turmoil continued as it became Nicolás’ turn to take the reins of the family winery. Against a challenging backdrop of political and economical stability, Nicolás concentrated on expanding distribution throughout the country. In the early 1980s, Nicolás took a short sabbatical and visited the University of California at Berkeley. That was also the time when Californians decided to defy Europe by creating a Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay that could rival the best French wines.

Nicolás then returned to Mendoza with a vision – a California vision. He sold his table wine-producing company and kept only Bodegas Esmeralda, the fine wine branch and many people thought he was out of his mind. But instead, Nicolás laid the groundwork for the country’s preeminence on the world’s wine map today. He discovered the best places to plant vineyards in Mendoza. He felt that the only way he would make a leap in quality would be to push the limits of vine cultivation in Mendoza.In 1992, he settled on Gualtallary Alto, at 5000m, it’s the highest and westernmost spot in Tupungato, cooling, but protected from frost by the nearby mountains. It has a slight slope and a small hill. He called the vineyard Adrianna, after his youngest daughter.

His own vineyard manager told him that Malbec would never ripen in the high-altitude elevations at Gualtallary. But it did, and beautifully. In fact, Nicolás found that Mendoza was exceptional for vine growing, with each high-altitude valley providing a unique flavor and aroma profile of the same varietal. He found that the poor soils near the Andes, discarded by the original European immigrants because of their low fertility, were actually ideal for quality viticulture; they provided a terroir where vines had naturally low yields and ripened slowly over the summer, making wines of great balance, elegance and deliciously soft tannins.

Then came the challenge of what to do with Malbec. Nicolás did not readily share his father’s—or his grandfather's—confidence in Malbec. Most of the wines admired by wine collectors around the world at that time were made of either Cabernet Sauvignon blends or Chardonnay, and Nicolás wondered if Malbec would ever be able to reach such heights; Indeed, this was important to him in his principal goal of making Argentine wines that could stand with the best of the world. But after his father Domingo died in 1985, Nicolás made it his mission to see if his father’s intuition was right. It took 5 years of working on the 85-year-old Angélica vineyard before Nicolás was satisfied enough to make a Catena Malbec in 1994. It was ranked as Argentina’s #1 Malbec in the Wall Street Journal’s first-ever feature on Malbec. It took another decade after that for Malbec to become a well-known wine varietal around the world.

This is the family’s dedication to unlocking the secrets of Mendoza and the story of Argentine wine.